Mosquitos, Drills & The Holy Names: Trying to Meditate in Noisy Mexico

Ever try to get quiet inside while the world keeps yelling? Not just in your head either, but outside too, like mosquitos whining at your ears, kids screaming, and someone (somewhere) always drilling.

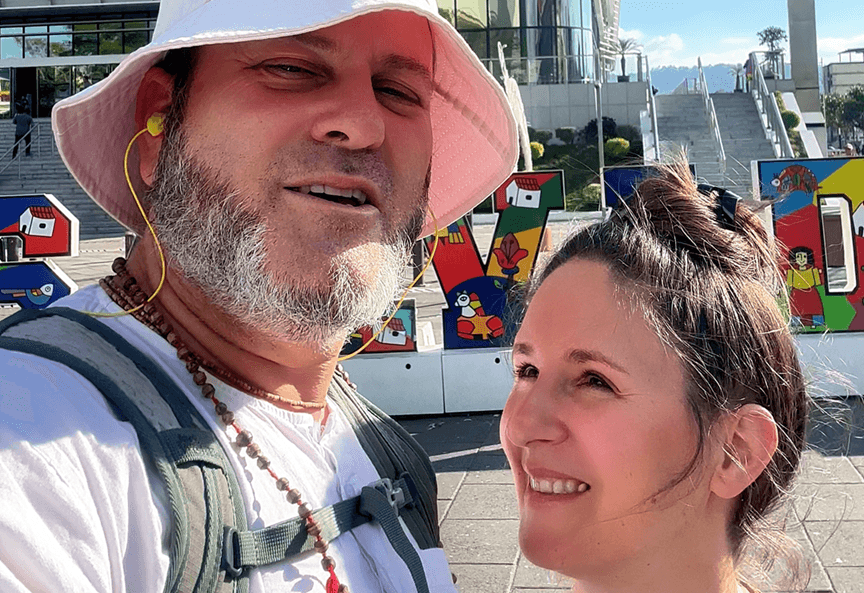

That’s the vibe in Valladolid, Mexico, sitting on broken chairs in the courtyard of the Convento de San Bernardino de Siena, a big old Franciscan monastery in the Yucatán. Two tired but grateful travelers, still laughing through the aftershocks of “Montezuma’s revenge,” talking about asteroids, underground water, the miseries of material life, and the soft, steady lifeline of chanting God’s names.

A Franciscan courtyard in Valladolid (and broken chairs)

The setting matters, because it’s part of the teaching. The Convento de San Bernardino de Siena is one of those places that feels simple and heavy with history at the same time. White stone, open air, a courtyard that holds sound, footsteps, wind, insects, and yes, the occasional power drill.

If you want a bit of background on the site itself, here’s a helpful overview of the convent and its history: Convento de San Bernardino de Siena in Valladolid. Another solid read, with a traveler’s angle and a few concrete details, is Convento San Bernardino, Valladolid.

But in the moment, it’s not a museum blurb, it’s two people sitting there thinking, “We’re in a monastery courtyard and it’s still loud.” Which is funny, and also kind of perfect.

Because the point isn’t to find a world that’s finally quiet. The point is to find a way to remember God even when it’s not.

The Yucatán is full of holes (and you’re standing on them)

Then the conversation swings wide, out of the courtyard and down into the earth.

The Yucatán Peninsula is famous for its cenotes, those freshwater sinkholes and caves that feel like hidden wells of clear blue life. And the way it’s described is so blunt and vivid it sticks: the ground is like Swiss cheese, full of holes. Fractures. Caverns. Water below.

In their telling, it goes back to a massive asteroid impact, the kind of event that changed the planet and wiped out huge amounts of life. The impact and its effects (fractures, geology, water systems) become this living metaphor: you can walk around thinking the ground is solid, while underneath you there’s an entire unseen world.

And it’s not just poetic. They’re standing near a large cenote that once supplied water to the monastery, peering down into what looks like a deep well of water, and it hits them: “We’re basically walking on top of openings that could collapse.”

Maybe it’s 100 feet, maybe it’s less, the point lands anyway. One small earthquake and down you go.

It becomes a kind of honest laugh, but also a reminder: life feels stable right up until it doesn’t.

The four miseries of material life (the list that doesn’t go away)

From cenotes and collapse, the talk shifts into a classic teaching from bhakti and Vedic thought, the four miseries of material existence. Not as a gloomy lecture, more like, “Look, we’ve been living this the last few days.”

1) Miseries from your own body

Your body can be a blessing and a hassle in the same hour.

Sometimes it’s sickness. Sometimes it’s travel stomach. Sometimes it’s exhaustion. Sometimes it’s a cough that won’t leave, hanging around week after week, making you choose quiet chanting because talking triggers coughing.

The body is part of the deal here, but it comes with problems built in.

2) Miseries from your own mind

This one is almost too relatable. The mind keeps you awake at night. It spins stories. It replays conversations. It panics. It judges. It just won’t stop.

That’s not a rare spiritual problem, it’s a Tuesday.

And it counts as suffering too, even if nothing “bad” is happening outside. The mind can make a peaceful room feel like a war zone.

3) Miseries from other living beings

This part gets funny because it’s immediate and specific.

Mosquitos. Kids screaming all day. The guy drilling in the distance. Noise that follows you even “into the middle of the Yucatán.”

And yet, there’s tenderness in it too, because they notice the crickets, how their sounds can be strangely beautiful, like a tiny orchestra made out of back legs and night air.

Other beings bring annoyance and beauty, sometimes both at once.

4) Miseries from nature (the big calamities)

The last category gets serious fast: earthquakes, hurricanes, typhoons, volcanoes, tidal waves, mudslides, rogue waves, quicksand, all the big forces that remind humans they’re not in charge.

They also mention “demigods,” meaning higher beings (in the Vedic worldview) entrusted with running aspects of the universe. Whether you interpret that literally or symbolically, the lived result is the same: storms happen. The earth shakes. A wave takes a village.

And even if you’re not the one getting hit, your heart breaks when people you love are in it.

Then they land on the deep repeating loop underneath all of it: birth, old age, disease, and death. That cycle is what makes the material world feel like a place you can’t fully settle into. You can’t renovate your way out of it.

“As long as we stay here, we can’t escape it.” That’s the line. Not hopeless, just clear.

The four problems of the conditioned soul (why we keep tripping)

Right after the “four miseries,” they bring up another set: the four defects of the conditioned soul. It’s like saying, “And even if the world were easier, we’re still carrying our own broken compass.”

These are presented as a chain, one leading to the next.

Imperfect senses

The senses don’t give perfect information. They don’t see clearly. They chase the wrong things. They grab at what looks good now, even if it hurts later.

And in the bhakti framing, the senses become clearer when they’re directed toward loving service to God. Without that, they mislead us.

Mistakes

If your senses are off, mistakes follow. Wrong assumptions, wrong choices, wrong priorities.

Not because you’re evil, but because you’re limited.

Illusion

Then comes illusion, the deep one: thinking “I am this body” and “I am this mind.”

They call the body a “meat puppet suit,” which is ridiculous and also kind of true. You live inside it, you steer it around, but it isn’t the whole you.

Cheating

And once you’re in illusion, cheating happens. Sometimes outwardly, sometimes inwardly.

There’s a sharp little honesty here: you can cheat others because you’re already fooled yourself. You become “the cheater and the cheated,” both ways.

It’s not said with shame, it’s said with humility. Like, “This is the human condition, so why pretend we’re above it?”

The “bag of stuff” talk (and why it’s meant to wake you up)

At this point they bring in one of their favorite teachers, Gour Govinda Swami, remembered as powerful and funny. He has this blunt way of describing the body to break the spell of vanity and obsession.

A body, in his framing, is basically a bag of pus, blood, bile, mucus, stool, urine, bones, all the bodily ingredients we try not to think about.

And the image gets even more intense: imagine taking everything inside your body and putting it into a clear plastic bag. Would you admire it? Would you post it on social media? No. You’d label it medical waste.

So why do we worship the container?

The point isn’t self-hatred. It’s perspective. It’s trying to stop the mind from making the body into a god.

Food, simplicity, and offering (not worshiping “stool”)

Then the talk turns toward food, with some humor and some self-correction.

They mention how modern “foodie” culture can become its own kind of worship. Not appreciation, but obsession. And since food goes in one way and comes out another way, it’s easy to see how strange it is to make eating your main spiritual practice.

They’re clear about something important though: you do have to keep body and soul together. This isn’t about starving or punishing the body. It’s about eating what’s needed and keeping it simple, “so that others may simply live.”

Vegetarianism comes up here too, but again, it’s not used like a badge. The line is direct: the goal isn’t to be vegetarian or vegan, the goal is to be pleasing to the Supreme Being.

In their bhakti practice, part of that is offering food, foods in the “mode of goodness” (sattvic foods), and especially prasadam, food offered in devotion. They describe offering through disciplic succession, through saintly persons, through guru, through the mercy of Lord Chaitanya and Lord Nityananda, and to Radha Krishna. It’s relational, not performative.

They also make a careful point about harm: even picking a leaf involves killing at some level. Just breathing involves killing microscopic life. So the practice becomes doing the least harm possible, while staying prayerful and honest about what it means to live in a world where survival has a cost.

Chanting in the age of quarrel (the “no other way” refrain)

Noise outside. Noise inside. Harm you can’t fully avoid. A world full of holes.

So what’s the steady practice?

Chanting.

They call this time the age of quarrel, chaos, hypocrisy, and confusion (a classic way of describing Kali-yuga in Vedic tradition). And the remedy they return to is simple and repetitive, on purpose:

Hear and repeat God’s names. No other way. No other way. No other way.

Not said as a threat, but as comfort. Like, “You don’t have to solve the whole universe. You can do this one thing, again and again, and it will carry you.”

They also share a sweet sense that many “high beings” come to this world because in this time we have access to the holy names, given by saintly people, and by God through Lord Chaitanya. So the invitation is plain: accept the gift.

Japa beads as a lifeline (and why the beads you use are the best ones)

A very grounded part of the video is how personal the chanting becomes.

They talk about japa mala beads given by a guru, described as a lifeline, even “a ticket to the transcendental realm.” Not jewelry. Not a prop. A tool for staying connected.

One of them shares how they keep beads in hand while walking, chanting constantly, needing that tactile feedback. They also mention a special set of beads given by a friend in Mexico City (CDMX), beads that had been taken to Varanasi and touched to (dipped in) the Ganges, “Mother Ganga,” honoring not just the physical river but its spiritual aspect.

There’s gratitude here too, directed toward friends, Fernando and Caro, who hosted them and supported their mantra meditation class, with Fernando playing music.

Then comes a line that’s worth sitting with: the best beads are the beads that you use. Not the prettiest, not the most expensive, not the most “authentic,” but the ones you actually chant on.

How they chant (simple, audible, beat by beat)

They encourage chanting out loud, clearly, syllable by syllable, so you can hear what you’re saying. One name per bead, moving forward, letting sound anchor the mind.

It’s gentle and practical, especially if your mind is noisy. Hearing yourself chant can be like holding onto a handrail.

An interfaith pause: the Jesus Prayer and a shared longing for mercy

There’s also a warm interfaith moment that feels very natural, not forced.

They mention the Jesus Prayer, learned from a Russian monk, from the book The Way of a Pilgrim: “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me, a sinner,” with a longer form, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.”

It’s offered as a real option if someone feels more connected to that tradition, especially during the Christmas season. They point out that wherever there’s life, there’s a soul (jiva), and all souls are children of the same Supreme Being. Jesus is honored as a very good son.

And then they add something bold, from their own faith: chanting the maha-mantra includes all other prayers within it, and leads to the highest goal of human life.

You don’t have to agree with that claim to feel the heart of it: keep calling out to God with sincerity.

What the Maha Mantra is asking for (in plain words)

They circle back to the meaning of the Hare Krishna maha-mantra, keeping it simple:

“O energy of the Lord, O Lord, please engage me in loving service to You.”

Not “make my life easy.” Not “give me my wishlist.” Not even just “save me.”

It’s a request for service, for relationship, for love. They describe it as beyond religiosity and beyond salvationism. It’s about arriving at the platform of loving service to God and God’s devotees.

And there’s a sober reminder tucked in there too: one day you’ll be on your deathbed, unable to open your mouth, “croaking,” and in that moment you’ll want your mind trained to remember something higher. Practice now is practice for then.

Conclusion: chanting when life is loud (and the ground feels thin)

Sitting in a monastery courtyard in Valladolid, with mosquitos and drilling and travel sickness still fresh, the message stays oddly soft: keep chanting, keep remembering, keep it simple. The world has its four miseries, and we carry our four defects, but the holy names can still be a steady thread through all of it.

If you’ve got beads, use them. If you’ve got a voice, use it. Whisper if you need to, chant loud if you can, but keep returning to the names of God like they’re home. And if you’re reading this in a noisy season, try one small act of remembrance today, then see what changes inside when you do it again tomorrow.

TLTRExcerpt

Recent Posts

Last Night in San Salvador: Christmas Blessings, Winter Solstice & Chanting With a Sweeter Mood

We found El Salvador’s National Library, Then The Cathedral Pulled Us In

Our Tiny San Salvador Video Turned Into a Whole Blessing (Starbucks Changas and All)

We Saw Christ With His Arms Wide Open, So We Talked About Love (No Labels)